Buying a New Saddle? Read This First

by Colleen Meyer

This is the first in a series of articles from Master Saddle Fitter, Colleen Meyer.

Finding a saddle that is right for both horse and rider can be a baffling experience that sometimes results in an expensive disappointment -- or worse, a series of them. The array of saddles on the market today is vast, if not particularly deep, and even an exceptionally determined shopper will be hard-pressed to try them all. So, what can riders do to reduce the randomness of this process?

Several years ago, a horse owner presented me with a meticulous spreadsheet of 28 saddles she had tried without finding a single one that worked for her horse. She was sure that she wanted a dressage saddle with a deep and secure seat, a narrow twist, and a flap that would help her maintain a perfect leg position. She had tried every saddle that she could find meeting these requirements, either in a wide or an extra-wide width for her thick-backed young warmblood. However, according to the notes on the spreadsheet, the saddles either rocked,rolled,slipped,pinched,bounced, pitched,yawed,tottered, or wobbled. One after another,these saddles shut this sensitive young horse down. On top of that, they cost a fortune to ship back and forth.

Unbeknownst to this data-driven buyer, about 26 of the 28 saddles detailed on this epic document were, from the horse’s standpoint, essentially the same saddle wrapped up in 26 different skins. The information she had about horse fitting was never going to be sufficient to reduce the randomness of her search. In a way, she was lucky that her horse was quite free in expressing his opinion about these ill-fitting saddles, as some horses don’t really speak up when their saddle does not fit correctly, which in the long run, is worse.

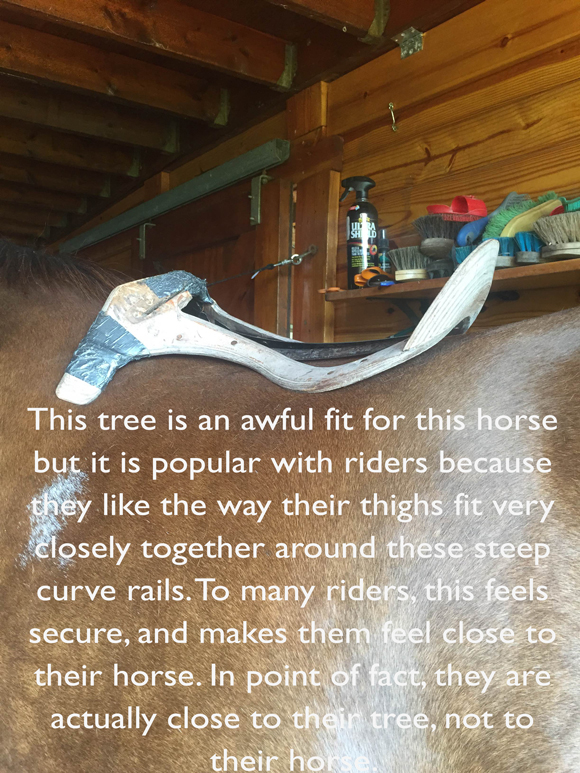

Saddles are marketed towards riders rather than horses, and since many riders have specific ideas about the feel they want, many popular saddles are designed primarily around giving riders just that. What the riders want is not always equivalent to what the horse wants, but riders generally have an easier time figuring out what saddles they like to ride in rather than what is optimal in horse fit.

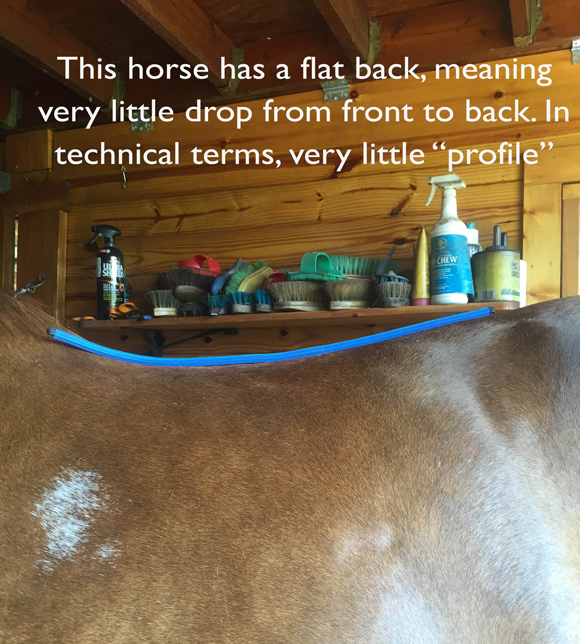

In the case of the saddle seeker, many of the 28 saddle trials so carefully documented on her spread sheet were more or less acceptable to her, but none pleased her flat-backed, wide horse. The owner was understandably frustrated, and wondered at this point whether there were any options left to her other than a fully custom-made saddle;frankly, if this option really was an ironclad solution, internet bulletin boards would not be wallpapered with cautionary tales about dashed hopes for finding the perfect saddle.

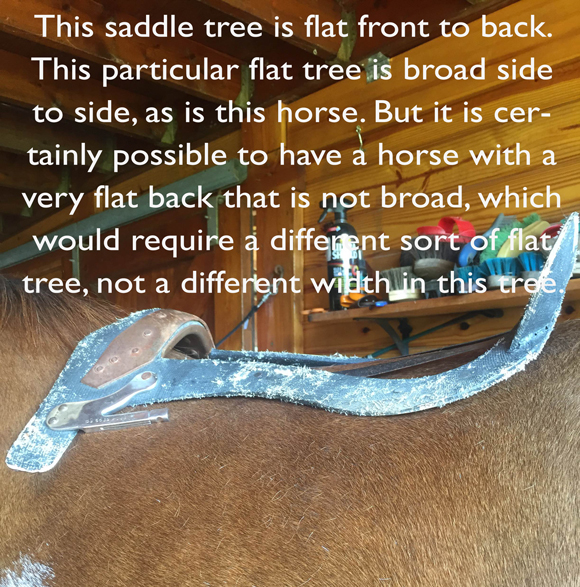

The crux of the problem was that this saddle shopper had begun by filtering her choices through a set of parameters based largely on her preferences as a rider. All of the saddles that this saddle seeker tried were at least a wide, and some were extra-wide, yet none worked as expected for her wide horse. If she had been able to see the actual bearing structures inside the saddles she was trying, and to compare the shape of these trees to the actual shape of her horse, she would immediately have realized that a medium-wide in a flatter, more open-headed tree with short tree points can often fit far wider than an extra-extra-wide in a curvy, steeply-arched tree with longer tree points.

Tree shapes are immensely variable front to back, side to side, and over and under, but since her saddle choices were driven by her desire for the feel of a deep seat with a narrow twist – and those features are closely related to tree shape -- she was, in effect, trying to clip a clothespin to a billiard ball.

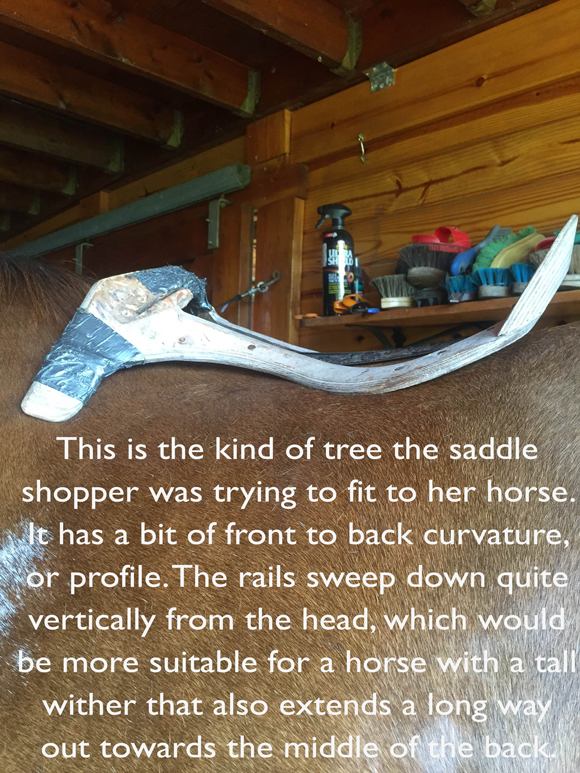

In my many years as a saddle fitter, I have often (as in every day) encountered variations of this experience, as riders are conditioned to assume that the rider feel and horse fit are independent variables. In this instance, the search was on for a deep, curvy seat with a narrow twist for the rider, and a tree wide and flat enough to fit a lovely, elegant, and talented young…sausage. Over and over again saddle shopper unwittingly returned to a specific shape of tree -- a tree that is fairly curvy with closely-spaced, steep, vertical rails. Why? Because that is the kind of tree shape that commonly provides the rider the feel she craved. If she was riding that shape of horse -- angular, high-withered, slope-backed, roof-shaped -- this might not have been a big problem. In reality, her horse had a short, broad back, with low, dome-shaped withers, similar to a better class of Thelwell.

If saddle buyers were able to approach the saddle search with at least some understanding of what actually distinguishes one saddle from another -- on a technical, reality-based level rather than what is dimly seen through the pea-soup mists of marketing -- it would be easier to reduce the randomness of the process. Instead, people often start, as in this instance, by defining their dream saddle. Wittingly or not, they often assume that all the features that a particular rider might want in a saddle are somehow completely distinct from the specifications that affect horse fit. While this isn’t always the case, the saddle industry does little or nothing to dispel this misconception.

Saddle companies are, after all, in the business of selling saddles to riders, not to horses, and most of what they have to say about the superiority of their products is quite vague on exactly how it is possible for a given saddle to put every rider in a perfect position on whatever shape of horse they ride. I have yet to see a saddle ad that highlights the very real constraints of geometry in tree engineering, or the tradeoffs that might sometimes have to be made for technical reasons when trying to fit a single bearing structure to both human and horse. Saddle ads -- and for that matter the “rules” in common use for fitting saddles -- are pretty slack in their handling of hard subjects such as gravity, force, tree geometry, and those pesky laws of physics that can be such a nuisance in the saddle business.

There are many challenges to making a single piece of equipment fit and function perfectly for two individuals from completely different species. One very basic challenge is that our vocabulary for describing saddles (and horses too, for that matter),is inexact to say the least. The term “wide” is so vague that it’s essentially meaningless, and the more precise sounding “36 centimeters” is no better at describing tree fit, since this numerical measurement only describes the distance spanning the bottom end of the tree points instead of the following aspects: the diameter of the head, length of the tree points, angle at which the rails are set on the fore arch, spacing between the rails, diameter of the seat, or any of the other varied and complex dimensions of a tree that determine the overall shape and fit of the saddle.

In reality, tree shapes vary immensely from front to back, side to side, and over and under. It is futile to put a nominally wide, but steep and curvy tree on a stocky horse with a nearly flat back, because nominal width as a tree measurement is pertinent only to a specific tree, and every shape of the tree has a distinct geometry.

Shape isn’t such a hard concept to understand, but it isn’t the way we are used to describing the fit of trees -- more’s the pity. Imagine mathematics with a comparably primitive lexicon, in which the definition of a triangle is “three lines joined by pointy ends,” and equations are “numbers separated by symbols that tell you what to do to get the answer.” Does this sound far-fetched? Then consider the sentence that people who are looking for a saddle frequently use to describe a horse: “He always measures wide.” Always. Measures. Wide. The only real information conveyed in that sentence is that the horse is male.

Let’s start with Always: If we really could always measure horses, it would involve measuring them while they are loaded with a rider and working through a full range of motion. There are a number of interesting tools and devices in use by saddle fitters to measure a horse’s back with such precision that this stationary contour can apparently be replicated back in the factory in order to produce a saddle perfectly suited to the shape of the horse. The problem is that the back changes shape when weighted with a rider, and it changes shape throughout the range of motion. We don’t yet know a lot about how horses’ backs change shape when carrying a rider through a full range of motion, but we do know that the shape of a dressage horse’s back is different in a piaffe than in a free walk or an extended trot. In a jumper’s back, the changes in shape are even more extreme between the approach to the jump, the bascule, and the landing. Therefore, it seems to me, the back that is being so assiduously measured for a precise custom-fit can never really replicate the shape of the horse’s back when it is carrying a rider and is in movement.

Measures: Unreliable! Whether a horse is being measured with a bent coat hanger or an antique sextant with magical properties, the only thing being evaluated is the external contour. This method of measuring can sometimes be deceptive, as it reveals nothing about what lies underneath the surface of that contour; whether it’s flabby or hard,and if there’s a high platform of bony support from the rib cage, or a great, long plunge from the peak of tall wither bones to the rib cage far below.

Wide: Many saddles are sold as wides, though some go by a numerical measurement such as 36 centimeters, without regard to the shape and dimensions of the arch or the overall fit from front to back. This conveys no more useful information about the shape of the bearing structure or the fit of the saddle than saying, “it’s brown.”

In saddles, as with riders’ pants and boots, the best fit for unhampered performance through a full range of motion is not necessarily the most precise fit; it’s a fit with enough tolerance to allow the horse’s back to change shape in motion without being trapped between the rails of the tree at the base of the withers, or blocked by an encounter with too much curvature in the structure of the tree when the well-engaged back wants to become rounded as it rises up. No matter how precisely the tree and panels conform to the shape of the static horse, the fit cannot be equally precise under all conditions of use.

The key to a tolerant fit seems to be to find a blessedly happy medium for a given shape of a horse’s back: a tree that is spectacularly average for a particular shape of horse; or a tree that isn’t “too anything” for the back it’s sitting on: not too steep, flat, curvy, wide or narrow. Think of a marvelous pair of hiking boots that support and protect your feet without either crowding your toes or letting your heels slosh around. Do any such trees exist? Oddly, yes, and many of them are old-style trees, dating back to a time when wood trees were made on forms that somewhat resembled horses’ backs, as opposed to many of the trees used today, which are largely driven by rider feel.

Once you strip a saddle down to its foundation, it becomes apparent that what keeps a saddle stable throughout the full range of motion starts with a good match in shape between the bearing structure in the saddle, which is the tree, and the shape of the back that tree is going to be used on. It is futile to put a nominally wide, but steep and curvy tree on a stocky horse with a nearly flat back, although, this is a shockingly common practice.

In the best of all possible worlds (as determined by me, of course), this saddle shopper should initially have narrowed her universe of choice for this tubular, flat-backed youngster to saddles built on trees of a suitable shape for a wider, flatter back. (In British saddlery, these are often called Highland and Cob or H&C-type trees.) She could have then moved on to determine the best width, panel configuration, etc. Once she had a selection of saddles that were likely candidates for her horse, she could have picked one she liked or could have learned to like. Riders almost always DO learn to like, and maybe even love, a saddle that really and truly fits their horse.