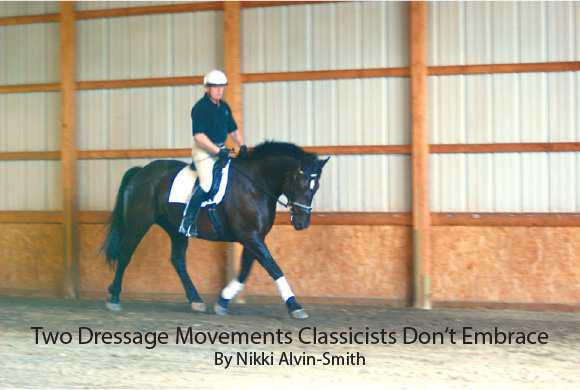

Two Dressage Movements Classicists Don’t Embrace

By Nikki Alvin-Smith

Dressage aficionados worldwide study the theory of the art of classical training with intense passion and the true classicists will argue over the inclusion of two dressage training movements and their place in the ancient equestrian pursuit that is dressage. Do you know which movements these are? And do you use them? Do you know how to train them and when they should be dismissed from the daily training routine and why?

Surprisingly many dressage competitors are unaware of the actual reasons the movements they earnestly train their horses to perform are included in the tests.

As with any sport the study of the theory behind what you do is very important to understand if you wish to be successful. In dressage you will often hear talk of Classical Dressage versus Sports Dressage. In my humble opinion, there should not be a difference. However, in reality the required dressage movements in the show ring do differ from the training practices of the old Masters.

The most common discussion concerning actual movements and their use in dressage and other flat work training, centers primarily around the use of the turn on the forehand and the leg yield. The latter movement is required in First Level tests and is often both judged and ridden incorrectly. It is a widely held belief that an incorrect execution of this movement can physically damage a horse. This is a viewpoint I share.

So let’s take a look at these movements, learn how to do them correctly and find out why classicists like myself believe they should be used only briefly during the development of the dressage horse to Grand Prix.

So let’s take a look at these movements, learn how to do them correctly and find out why classicists like myself believe they should be used only briefly during the development of the dressage horse to Grand Prix.

When you begin work with your horse in dressage you may have done some groundwork and taught the horse to step away (without fear) from the tap of the whip on his side and to move away from pressure behind the girth effectively turning around his forehand. The horse needs to move away in a lateral movement from the rider’s leg and this is a good place to start.

However, the reason classicists do not like to include this movement is because in all other aspects of dressage the horse is always asked to go forwards as well as sideways. In the turn on the forehand however, the horse is prevented from forwards movement. Another issue is that in a turn on the forehand your horse’s center of balance is shifted to the front of the horse i.e. the front legs and shoulders. This is the opposite of what we ask the horse to do in dressage, which is to shift his weight backwards.

When training our young horses I will teach them the turn on the forehand (it is also a useful tool for the horse to know if you are mounted and need to open and shut a gate). I will use it just until the horse understands he needs to move away from the leg pressure in a sideways direction and then discard it.

Here’s how to do it:-

Start with a turn on the forehand to the left as this is generally the easier direction for your horse. Make sure you are sitting nice and square on your horse and that he is standing in a solid square halt. While your left leg stays on the girth take your right leg three inches behind the girth. Your left rein will keep the horse’s neck straight and you will vibrate the right rein slightly to encourage the horse to maintain flexion through his poll. You are asking your horse to turn 180 degrees and change his direction. Facing the horse toward the wall or fence can be helpful.

When you begin you will start by taking the right rein and flexing him slightly to the right. Apply leg pressure from your right leg but keep some pressure on the inside rein and your inside leg quietly at his side. Be certain you stay sitting upright in the saddle and do not lean as your horse turns.

At times in clinics I have asked a student to show me their turn on the forehand and the result is a horse swishing his tail, head in the air and nothing happens. The best way to correct this issue is not from the saddle as the horse clearly has no idea what is expected of him. It is best to hop off the horse and direct the movement from the ground. To do this, stand facing the back of the horse at his shoulder. Take the inside rein toward you with your closest hand and ask for slight inward flexion and then reach three inches behind his girth and push with your hand to encourage him to step away from the pressure. You can also use the handle end of a whip to push or tap. As soon as he takes the slightest lateral step praise him and ask again. Do this on both sides of the horse. Once this is achieved he should understand the aids from the saddle.

The turn on the forehand should be taught only when the horse is already trained to the degree he moves readily forward of the leg in walk, trot and canter and can maintain his balance, straightness and rhythm in each gait and transitions are smooth and from back to front.

The turn on the forehand should be taught only when the horse is already trained to the degree he moves readily forward of the leg in walk, trot and canter and can maintain his balance, straightness and rhythm in each gait and transitions are smooth and from back to front.

Now your horse understands he needs to step away from the outside leg pressure you can work on the leg yield. In the leg yield the horse will have his head positioned in the opposite direction to his line of travel. The ideal line of travel is a diagonal line and if used at the track or on a circle the angle is 35 degrees. Riders find it hard to ‘direct traffic’ and follow the correct line when they are beginning lateral work and for students with his issue I have found it useful to spread a line of shavings on the arena in the diagonal line where I want them to execute the movement. This helps them learn the correct angle.

While I use this exercise briefly in the training of a dressage horse it can be very useful later for loosening a stiff horse, reminding a horse to move away from the leg and to correct issues with taking a correct lead at the canter.

For the more excited horse it is best to start this exercise at the walk, where he has time to think. For the phlegmatic horse it is best to start this exercise at the trot where the forward thought and energy is most accessible.

It is imperative that the horse’s spine is almost parallel to the wall with a very slight lead of the shoulders i.e. straight and that the only flexion to the opposite direction of travel is at his poll and NOT through his neck. Judges that mark down riders for not demonstrating enough ‘bend’ are incorrectly schooled in their judgment and in the benefit of this movement.

The rider should sit squarely in the saddle and always endeavor to maintain their shoulder angle and own spine to match that of the horse in any lateral movement. Hence in the shoulder in the rider’s shoulders should remain square as the horse’s spine should stay straight.

The leg position for the rider’s legs is the same as the turn on the forehand. Once again the horse will be flexed at the poll only (not the neck) away from the direction of travel. So for example in a leg yield left, the horse will look to the right. The rider’s left leg will remain on the girth and quietly tap to maintain forward motion, while the rider’s right leg will be three inches behind the girth (without bringing the heel up, just bring the leg back and turn your toe slightly to the outside when you tap). The left rein will support the horse forming a ‘wall’ to which the horse will move. The left rein will not be held in a stiff manner but offer steady and light half halts to encourage the horse to move his shoulder to the left. Both the left rein and left leg are mostly passive aids at this point in training. The rider’s right leg will be taken back and tap and release, tap and release on the horse’s side to ask for the sideways movement. If he does not respond to the leg then add the tap of the whip to support the right leg.

You do not want to teach your horse to lead with his hindquarters and as he learns to balance himself he may rush, lean or otherwise ‘mess up’ the movement. No worries. Simply ride him positively forward, go around and start again. If your horse does tend to lead with his hindquarters you need to use less pushing aid behind the girth and free the left rein when working to the left. Ensure you are not ‘holding’ anywhere e.g. in your set, thighs, calves or hand and picture the movement happening in perfect balance and execution.

You can complete the leg yield for just a few strides at a time and then ride forward. Do not ask for too much too soon. The horse needs to develop his hind leg engagement and suppleness in general, to execute several steps in a row. You can ride the movement with the horse’s head to the wall, from the center or quarter line to the track and later on circles. It is often easiest to learn the feel of the legs crossing over at the hind end of the horse, by training the movement along the wall. This allows the rider to gauge how much bend is too much in the neck and to learn how much support is needed from the outside rein to prevent too much neck bend in the horse. As a trainer of either horse or rider it is important to see what will work best based on the individual in front of you.

When working on the diagonal line, as with any lateral movement, I employ the three and three stride movement. That is three strides forward, three sideways, three forward etc. If you horse is truly on your leg aids and listening this will be easy. If he is not, you will soon find out! No problem. Just return to the more basic executions along the wall either nose to the wall (easiest) or nose to the inside of the arena and tail to the wall.

Many horses will be stiffer to one side than the other. On the soft or hollow side of the horse he will often bend his neck instead of just flexing at the poll despite your best execution of the aids. For a short period I ride these horses with their heads straight in the leg yield to their soft side until they have garnered the gymnastic strength not to be one sided.

Masters such as the great Spanish Riding School Director Alois Podhasky, dictate in their schooling that the leg yield should be mildly used and once the horse has understood he is to step away from the leg it should be discarded. The belief in regard to the biomechanics of the horse is that to ride the horse bent to the opposite direction of travel while offering lateral leg movement can cause strain and possible damage to the sacroiliac region of the back, the hip and hocks.

When a rider asks for too much bend in the neck during a leg yield the horse is contorted in a manner that is unnatural to his health and well-being.

Some horses are more athletic than others and all horses are differently designed in their conformation. While for some horses there may be little strain for others it could be considerable. Many years ago when schooling with Conrad Schumacher in Germany I learned much about working your horse to his conformational benefit. This is a subject for a whole other article or perhaps even a book! But suffice it to say it is extremely important never to override or over ask your horse especially in those early stages when your horse is less flexible and supple.

When working with Kyra Kyrklund she advocates not worrying about the horse’s head position at all in the beginning, just simply praising the horse when he moves away from the leg. Kyra begins the exercise on the diagonal and starts at the walk. With neophyte riders she also doesn’t suggest they ask for any flexion to the outside at all, as she wants them to leg yield, not rein yield. A good point and one worthy of consideration when you have a student that is holding a rein and consequently the horse is not going forward and a horse cannot be pulled sideways.

Remember these exercises are small stepping stages in your dressage training. Once the horse understands the lateral aids you can go to shoulder fore, shoulder in and what I call the lateral trinity: The Shoulder-in; the haunches-in & out: the half pass.

Let the fun begin!

Happy Riding.

About the author: Nikki Alvin-Smith is an international Grand Prix dressage trainer/clinician who has competed in Europe at the Grand Prix level earning scores of over 72%. Together with her husband Paul, who is also a Grand Prix rider, they operate a private horse breeding/training farm in Stamford, NY.