Proper British Riding in Kenya with Mrs. Carles Part 3

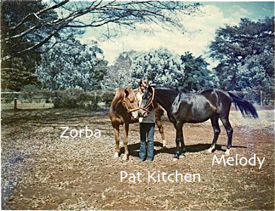

by Pat Kitchen

Mrs. Carles was the instructor that taught Prince Philip and Prince Charles to ride. When she moved with her husband from Britain to Kenya, her method of training was indeed, very British. Mrs Carles always poked fun at what Americans called English riding and what she called “British, proper English” riding. Americans ride a forward seat, the British ride a balance seat. Sitting straight up, shoulders back, but back straight not arched, relaxed. Head, shoulders, elbows hips and heels should all be in one line. Knees should line up with your toes. If you looked down you should not be able to see your toes.

Mrs. Carles believed 'artificial aids' were a sign of poor riding because it showed a lack of communication between the rider and horse. Crop and dressage whip were all that were needed and were used more as an attention getter, a way of keeping the horse focused.

She taught me mounting your horse should be swift and fluid. Reins crossed over your palm, grabbing a handful of mane with your left hand and right hand on the pommel, you mount up, lowering yourself quickly and quietly. Dismounting, still maintaining contact with horses mouth, both feet out of stirrups, swing your legs together and over the back of the horse and saddle, landing with your feet together. Americans grab the back of the saddle when mounting and when dismounting take one foot out of stirrup and keep the other in iron until on the ground. When mounting, when you grab the back of the saddle, you let go in order to sit making you off balance should your horse move.

In 'Proper British Riding' there should be very little space between the rider and their horse/saddle. You sat deep and gripped with your knees. Measuring stirrup length, before getting on, we measured finger tips to arm pit from saddle with stirrup leather and irons. Once mounted, legs dangling stirrup irons should come just below ankle bone. Hands relaxed just over pommel, elbows at your side.

Well schooled horse, and rider, should do as asked without artificial aids. Toes that turn out meant the riders leg was rubbing against the horses side, and just as with spurs, would lead to desensitizing that area. Americans , Mrs. Carles believed ride with their stirrups too short, legs forward, toes out and body leaning forward and she said there is no way you can properly feel and anticipate what your horse is going to do and react appropriately.

Even during a rising trot, aka posting, rider should barely come out of the saddle, maintaining close contact with the horse is of the utmost importance. Cantering, your backend should never leave the saddle and in fact, should move with the horse. Even walking up a hill, rider should lean forward to take some of the excess weight off horses rump.

Riders should be able to walk, trot, canter and jump, even if just a cavaletti, without stirrups. Americans put more weight in their stirrups and worry less about gripping with their knees. Should they lose a stirrup, they will most likely fall off.

Reins should be held with reins coming under pinky finger. This way you can maintain light contact. Americans tend to keep reins between ring and pinky finger so there is very little give. Contact with horses mouth should be very light, with the bit barely touching corner of horses mouth, but constant. Never loose, hanging reins because when and if contact is needed it will be sharp and painful to the horse.

When you could ride and follow all these directions Mrs. Carles would then allow us to attend horse shows. Which, as you can imagine, were a very different affair in Kenya than here in the U.S.A.

The horse shows that I went to were at Jamburi Park. The Easter Horse show was the biggest show of the year. Schools were British system, and were year round. 3 months on, 3 weeks off. Horse shows always seemed to fit into the school schedule.

There were no ready horse trailers, so our horses were ridden to show grounds by grooms the day before the show. There were stalls to rent on show grounds for those of us who needed them. The stalls made of split logs, were about 12x12 filled with a thick layer of wood shavings. Grooms, who stayed with horses at shows, boiled barley which would later be mixed with bran, a good dose of cracked oats (only given oats during show season) and a bunch of fresh chopped carrots.

Because Kenya was under British rule for centuries, the riding at these shows was “Proper English”

Proper attire was a must.

With the British riding system, anyone under the age of 16 could not show a horse, mount  had to be 14.2hh and under. We could not wear riding breeches or jumping boots, we were to wear jodhpur pants and jodhpur boots (called paddock boots in the US), white button down shirts, ties, tie clip, pony club pin (a four leaf clover, each leaf was filled in with colored cloth that showed what level of Pony Club you were at), velvet helmet, hair net and black jacket. Boots were spit shined, horses manes were pulled and braided, tails were pulled and trimmed. Horses hooves were also treated and shiny. Tack was clean, double bridle was not optional in dressage, a Pelham was acceptable in jumping.

had to be 14.2hh and under. We could not wear riding breeches or jumping boots, we were to wear jodhpur pants and jodhpur boots (called paddock boots in the US), white button down shirts, ties, tie clip, pony club pin (a four leaf clover, each leaf was filled in with colored cloth that showed what level of Pony Club you were at), velvet helmet, hair net and black jacket. Boots were spit shined, horses manes were pulled and braided, tails were pulled and trimmed. Horses hooves were also treated and shiny. Tack was clean, double bridle was not optional in dressage, a Pelham was acceptable in jumping.

Dressage riding was always done in a double bridle. If you were part of Horsemanship event, show jumping judges preferred a double bridle, but you could use a Pelham.

For dressage we walked down the white chalk center line, 4 point stop at the X, bowed and continued on our way. Judges should not see your hands or legs move. Control of your horse was done with your body and knees. If puffs of chalk did not show when you walked down center line, you would lose points.

We were expected to do flying changes, lead changes, pivots and side stepping. Horses head had to be high and tucked with perfect curve at nape of neck, nose should be perpendicular to the ground, no more no less. Horses had to be collected and centered/balanced with proper lead.

When riding the 20 meter circle, horses’ head and neck had to be in a smooth curve to the inside. During the rising trot rider would come down as the horses outside leg came down, with canter lead leg had to be inside foreleg.

In Horsemanship course the judges got up close and personal for sure. You were graded, not just on your riding and horses performance, but on yours and your horses’ turnout. Rider had to be properly groomed and dressed. Horses mane braided, tail pulled, tack clean, horse groomed, hooves picked. If any of these was not done, or not done well, you would lose points.

Show jumping was timed and there were a variety of jumps, including brick, hedges and water jumps. Average height of jumps was only about 3 feet. If our horse, even knicked the jump it was 1 fault even if nothing fell.

Show jumping was timed and there were a variety of jumps, including brick, hedges and water jumps. Average height of jumps was only about 3 feet. If our horse, even knicked the jump it was 1 fault even if nothing fell.

My 1st show, day 1, when my mount Zorba refused a jump I turned him back the wrong way. No one told me that if I crossed my own path it would count as a refusal. 8 faults right off the bat. That was a mistake I didn’t make again.

Our 2nd day we placed 2nd in jumping. I have no idea what my score in dressage was but got a 3rd overall.

It was a lot of fun but quite intimidating at the same time. Lots may have changed in Kenya since I lived there eons ago, but that British riding sticks with me and I hear Mrs. Carles remarks in my head when I am out riding to this day. She was brilliant.

(see earlier articles in our archives).